A short speech defending the role of the family has become Giorgia Meloni’s calling card at campaign rallies. “I am Giorgia. I am a woman. I am a mother. I am Italian. I am Christian. You can’t take this away from me,” she said.

The woman widely expected to become Italy’s first female prime minister in Sunday’s election is far from typical, however: A far-right nationalist accused by political rivals and experts of spreading white supremacist ideas, who advocates naval blockades to stop unauthorized migration from Africa, Meloni is also a committed J.R.R. Tolkien fan and has embraced the internet memes and music remixes of her famously fiery speeches.

Her victory, as the leader of a right-wing coalition, would make Italy the latest European country after Sweden to see a far-right party win power, months after Marine Le Pen staged a strong challenge to President Emmanual Macron in France.

Meloni leads the Brothers of Italy Party (Fratelli d’Italia, or FdI), a populist party with roots in Italy’s post-war fascist movement. Fdl is predicted to get 25% of the vote on Sunday, six times more than it received in the last election, in 2018, and enough to give it a clear majority in both houses of Parliament.

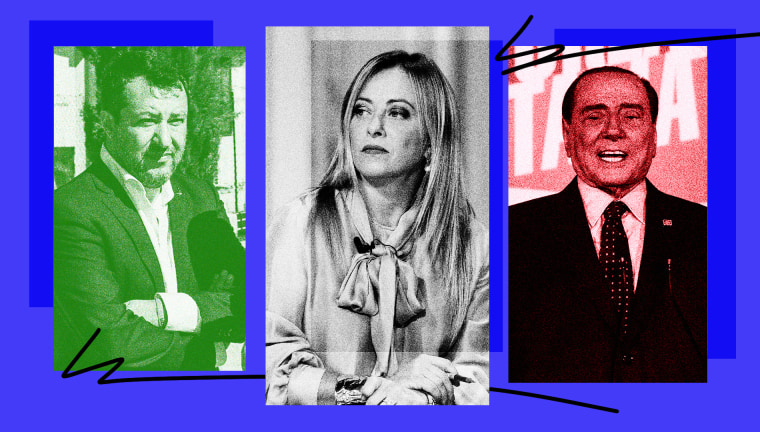

If elected, Meloni, 45, a mother of one, would head a coalition government made up of Matteo Salvini’s Lega Party (League) and Forza Italia (Forward Italy), led by 85-year-old media baron and former Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi, who is making another return to politics.

“What she’s trying to do is to both say she’s a traditional conservative but at the same time put within that frame ideas that are conspiracist, extreme and fascistic,” David Broder, a writer who lives in Berlin but specializes in Italian politics. His forthcoming book is titled “Mussolini’s Grandchildren: Fascism in Contemporary Italy.”

“Meloni is widely presented as the party’s face of moderation, because she’s a mother and can speak in cordial terms with other politicians, but she herself promotes white nationalist ideas,” he said.

Meloni’s office and the Brothers of Italy Party did not answer requests for comment by NBC News.

Meloni caught the public’s attention in 2019 when video of her “I am Giorgia” speech went viral. It was turned into an electronic dance music track by two DJs from Milan that has had 12 million views and counting on YouTube. Her autobiography was titled “Io Sono Giorgia” (“I am Giorgia”) and topped sales charts on its release last year.

She has compared her party to the center-right Conservative Party in Britain, but Meloni’s views will be familiar to anyone who has followed the rightward movement of Poland, the self-styled “illiberal democracy” of Hungary, and the nationalist populism of the Republican Party in the United States.

She has defended Viktor Orban, Hungary’s authoritarian leader, who is accused of demolishing democracy by packing his country’s judiciary and Parliament with supporters and giving himself the ability to easily create or change laws.

Meloni has bemoaned the chronically low birthrate in Italy — just 1.2 babies per woman, according to the World Bank, one of the lowest in the world — and spoken of a left-wing government plot to “finance the invasion to replace Italians with immigrants,” a main tenet of the “great replacement,” a conspiracy theory that accuses shadowy global elites of the wholesale importing of nonwhite migrants to majority white countries.

Her party’s manifesto says on its first page: “We are determined not to surrender to the economic, social, cultural and political decline of the nation,” before going on to link illegal immigration to drug dealing and urban decline.

“We live in a time in which everything we stand for is under attack,” she told the American conservative conference CPAC in February. In a speech on Tuesday in Palermo, she warned of the “violence” of Islam.

Brothers of Italy, whose name is based on the first line of the Italian national anthem, has roundly rejected any accusation of fascism or racial politics, describing such criticism as a left-wing smear from rival parties with nothing else to talk about. “In the DNA of Fratelli d’Italia, there is no fascist, racist, antisemitic nostalgia,” Meloni has said.

Her reputation may be largely positive — her personal approval ratings during the campaign have been higher than any other party leader’s — but the party’s membership continues to draw accusations of fascist tendencies.

This week the party sacked one candidate, Calogero Pisano, after a newspaper uncovered eight-year-old social media posts in which he praised Hitler as a “great statesman.”

Pisano, who was running in Sicily, in 2016 also praised someone for describing Meloni as a “modern fascist,” adding that Brothers of Italy had “never hidden its true ideals.”

“From this moment on, Pisano no longer represents [the party] at any level,” Brothers of Italy said in a statement Tuesday, Reuters reported.

Also this week, Romano La Russa, a member of the European Parliament and brother of the party’s co-founder Ignazio La Russa, was shown in a video that spread widely online doing a controversial salute at a funeral.

The salute, an outstretched right arm with a flattened palm, was adopted by Mussolini’s Fascist regime and then Hitler’s Nazi Party, although some Italian nationalists have since sought to reclaim it as an act of defiance.

Brothers of Italy did not respond to a request for comment on the incident.

Conscious of the shadow cast by her party’s past, Meloni released a video statement last month in English, French and Spanish denying there would be an “anti-democratic shift” or “authoritarian turn” should her party win power on Sunday. She has released similar statements in the past.

And, unlike some other right-wingpopulists, Meloni is a pro-NATO Atlanticist who supports the Western backing of the war in Ukraine. By contrast, her would-be coalition partner, Salvini, is a longstanding admirer of Russian President Vladimir Putin and has argued for scrapping Western sanctions on Russia.

Nevertheless, Meloni has faced questions throughout the campaign about the party’s fascist roots. Brothers was formed from the remains of the National Alliance, which descended from the Italian Social Movement (MSI), a fascist party formed by allies of Mussolini after 1945, and which has largely been restricted to the fringes of Italian politics and never been in government.

Mussolini, the original fascist leader, seized power in 1922 in his famous March on Rome and was prime minister until he was deposed in 1943, having turned Italy into a one-party dictatorship that supported Hitler in World War II.

National Alliance split from Berlusconi’s The People of Freedom Party in 2012 when its leadership, including Meloni, went on to form the Brothers of Italy, eventually adopting MSI’s tricolor flame logo with its fascist connotations, which it still uses today.

Speaking to a French TV crew while she was a MSI youth activist, Meloni praised Mussolini unequivocally. “Everything he did, he did for Italy — and there have been no politicians like him for 50 years,” she said in recently resurfaced footage.

“Italy never dealt properly with its history of fascism the same way Germany did with Nazism. In Germany Nazism has long been taboo. If a politician there makes a Roman salute, his or her career is over,” the historian Francesco Filippi told NBC News. His book “Mussolini Also Did a Lot of Good” dispels lingering myths about the dictator’s legacy.

The association with fascism is not enough to dissuade Meloni’s supporters, including young people.

“I believe she is popular now because she has been so coherent with her ideas and her basic values, which most Italians share,” said Maicol Busilacchi, 28, a law student from Potenza Picena, near the eastern city of Ancona, and regional president of Gioventù Nazionale, the youth wing of the Brothers of Italy.

He rejects any assertion that the party is far-right.

“The short answer is no. Fratelli d’Italia is something completely new. Many times in the history of the Italian right, the leaders have made changes to build a trustworthy party to govern Italy, “he said.

Although a minister under Berlusconi from 2008 to 2011, the multilingual, charismatic Meloni, from a working-class suburb of Rome, is relatively new to front-line politics.

The snap election Sunday comes two months after the government led by Mario Draghi collapsed after its unlikely mixture of left and right-wing ministers refused to implement a post-Covid economic stimulus plan.

The Brothers of Italy was the only party with significant support that refused to join Draghi’s emergency coalition, giving it the sheen of an unspoiled outsider as Italy faces a crippling cost-of-living crisis.

Meloni may succeed where others have failed. Le Pen, having presented herself as a moderate, conservative opposed to the liberal groupthink of French and European elites, won the support of both traditional right-wing and left-wing voters.

But in the end Macron held on to win 58.5% of the second-round run-off votes. Many Macron voters were unhappy with his record, but were willing to join “la barrage républicain” — the republican dam — to keep Le Pen and her extreme anti-migrant policies at bay.

In Italy, Meloni has similarly worked to soften her image and appeal to moderate patriots — but there won’t be any French-style electoral block on her ambitions, said Lorenzo Pregliasco, from the Italian polling company YouTrend, partly due to a fractured center-left opposition that failed to keep fragile pre-election cooperation pacts alive.

“We have only one round of elections — the coalition which is more cohesive and united has a very significant edge over the other coalitions and parties, and that’s the case for the right in Italy,” he said.

“You have the united front for the center-right, headed by Meloni and Salvini, and the other [left-wing] camp is splintered, fractured into at least three parts,” Pregliasco said. “In France all the non-Le Pen voters could consolidate behind Macron.”

Italy may be drawn to an authoritative figure in times of economic strife, Filippi said.

“Since the fall of fascism, Italians have kept looking for the ‘strong man,’ one with a strong personality that would take care of its people as a father of the nation. It happened with Berlusconi, for instance. And now it’s happening with Giorgia Meloni,” he said.

Voters who support Meloni are not necessarily fascists or from the far-right, Filippi adds. “Many are just disillusioned with politics, tired of the failure of the traditional parties from the left and right, and simply want to try something new and disruptive.”

Patrick Smith reported from London, and Claudio Lavanga from Rome. Matteo Moschella contributed.